By accident Richard was born with a predisposition he valued highly, knowing he was lucky. Of his "restless nature" he wrote, "I'm very grateful, because I wouldn't take $1,000,000 for it." It was precious to him because he had visions of the possible where others saw only walls.

He was extraordinarily gifted in disposition—his life attests to that, as it is one that few are able to parallel. People could only read about all he did and saw because they were bound to the morning coffee and evening newspaper of their days. In Halliburton they found somebody who had slipped the bonds holding them and with sometimes wild energy delighted in a life that for them was not only improbable but impossible.

In the 1920s and 1930s Richard Halliburton was one of the most famous persons in America, even more than Amelia Earhart, and today he is forgotten. He knew many people who would not fit in the handy boxes society offered them. He starred in a movie. He swam the entire length of the Panama Canal as the SS Halliburton. He climbed the Matterhorn in winter. He chatted with Herbert Hoover, was friends with F. Scott Fitzgerald. Halliburton met history makers like Lenin's widow and the man who shot the Czar. The man told him how the Romanov family was assassinated in a basement in Yekaterinburg. For years many believed Halliburton made up the story but he actually interviewed one of the assassins.

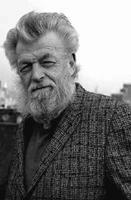

In The Eagle, of Reading, Pennsylvania on January 27, 1935, writing a column titled, “As Seen by Her,” Lilly Marsh said Richard Halliburton “is very nice looking. He has all of his hair—a nice grade of wavy auburn—and his swimming and mountain climbing and what not have certainly not done his figure any harm. He speaks with a pleasant if unidentifiable accent, and has the kind of charm that mows down audiences all in a minute. In all honesty, it is only fair to admit, that he could probably speak on the dreariest, dullest subject in the world, and still hold the attention of his listeners. He is very attractive. He has a great deal of personality, and I suppose it would be asking a little too much to require of him a sense of humor, also. We can’t have supermen walking the earth.”

Interviewed by Stan Welsh in 1994, John Booth, a retired Unitarian minister, tells the camera that the influence of Richard Halliburton on him was enormous. Booth traveled the world. He went to Rio de Janeiro, to the Rajong River in Sarawak. He lived in jungle long houses. He traveled in Indonesia. He met Anthony Brooke in Singapore in the late 1950s. Brooke’s uncle was the last reigning White Rajah of Sarawak, a country visited by Halliburton and his biplane pilot Moye Stephens in their round-the-world 1930s flight. During the visit they took the Rani Sylvia Brooke aloft. A Rani is rather like a queen. In those days, it was for her the thrill of a lifetime.

John Booth met Richard when he was a student at Cleveland Heights High in Cleveland, Ohio. Halliburton was there for a lecture on The Royal Road to Romance. When Halliburton walked to the lectern, girls shrieked as they later did with Frank Sinatra. He had charisma, recalled Booth, and was an “extra handsome young man.” Richard was introduced by the school principal. Halliburton talked about climbing the Matterhorn.

Born February 21, 1906, Richard's pilot Moye Stephens in his old age thought about how the course of his life changed by meeting Richard Halliburton. He thought back on those days with Richard, or as test pilot of the Flying Wing, or as a founder of Northrop Aviation. His life came close to many might-have-beens. He might not have given flying lessons to Howard Hughes. He might not have chummed with barnstormers and World War I aces such as Sandy Sandblom, Leo Nomis, Bud Creech, Eddie Bellande, Frank Clarke, Ross Hadley, and Pancho Barnes. He might not have known movie stars Richard Arlen, Ramón Novarro, Sue Carol, Reginald Denny, Wallace Beery, and Dolores Del Rio—or movie executives Cecil B. DeMille, Victor Fleming, Howard Hawks, and Howard Hughes.

With his intense energy and insatiable zest for living, Richard Halliburton undertook his next adventure, a voyage in a Chinese junk, Sea Dragon, from Hong Kong to the San Francisco World's Fair in 1939.

He and his crew were tossed in the junk by a fierce typhoon and were lost at sea.

Lost at Sea, the headlines proclaimed. This was big news to the world. Another famous adventurer had disappeared. The year before, Amelia Earhart with her navigator Fred Noonan had ditched a Lockheed Vega somewhere in the Pacific and was lost to everything but history. Before Sea Dragon's disappearance, across the continent, San Francisco to New York, families had huddled in living rooms, bent to their radio sets to hear of the junk's nine thousand mile progress toward the San Francisco World's Fair, opening in spring of that year.

On March 29, 1939, the Evening Independent of St Petersburg, Florida headlined a report from San Francisco, “Richard Halliburton Is Feared Lost at Sea.” The junk was two thousand four hundred miles from Hong Kong bound for Midway Island. The article explains, “The Sea Dragon was scheduled to reach Midway Island April 5.”

On March 29, 1939, the Evening Independent of St Petersburg, Florida headlined a report from San Francisco, “Richard Halliburton Is Feared Lost at Sea.” The junk was two thousand four hundred miles from Hong Kong bound for Midway Island. The article explains, “The Sea Dragon was scheduled to reach Midway Island April 5.”Also on March 29th in Dubuque, Iowa, The Telegraph-Herald stated that the “75 foot craft, with its crew of ten Americans and four Chinese, was approximately one thousand miles west of Midway,” and that “all ships, meanwhile, have been asked to keep a watch for the craft.”

The US Navy launched a search with float planes but neither survivors nor the Chinese junk were found. Richard Halliburton said early in life that he didn't want to die in bed. His life, he said would be active and vividly lived. He got his wish.

Click to read Don't Die in Bed: The Brief, Intense Life of Richard Halliburton.